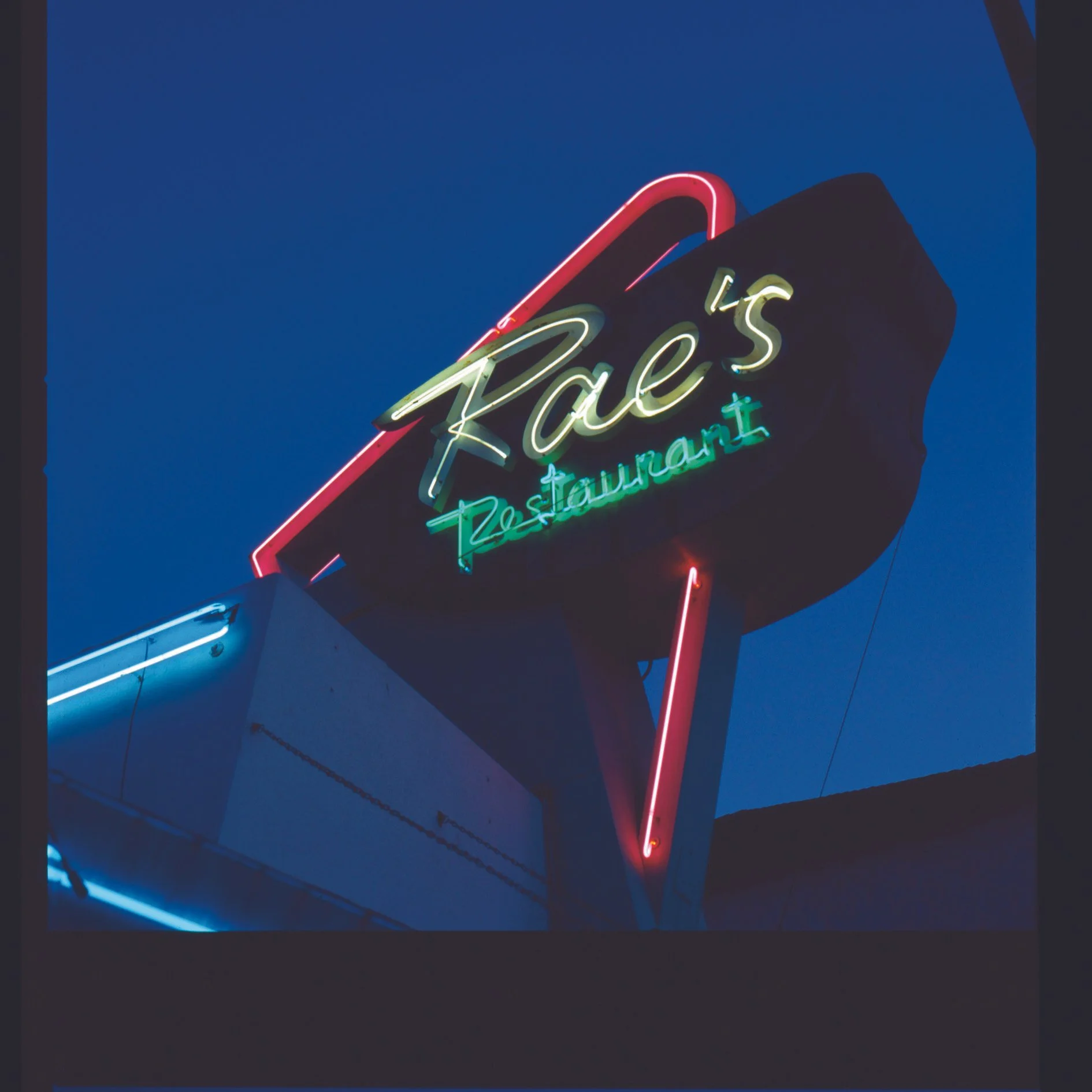

Love Lettering: Signs of Santa Monica

Photo by Alex Mebane

If you wandered down Lincoln Boulevard in the early 2000s, you might’ve spotted a man crouched under a rusted lollipop sign, vintage camera in hand.

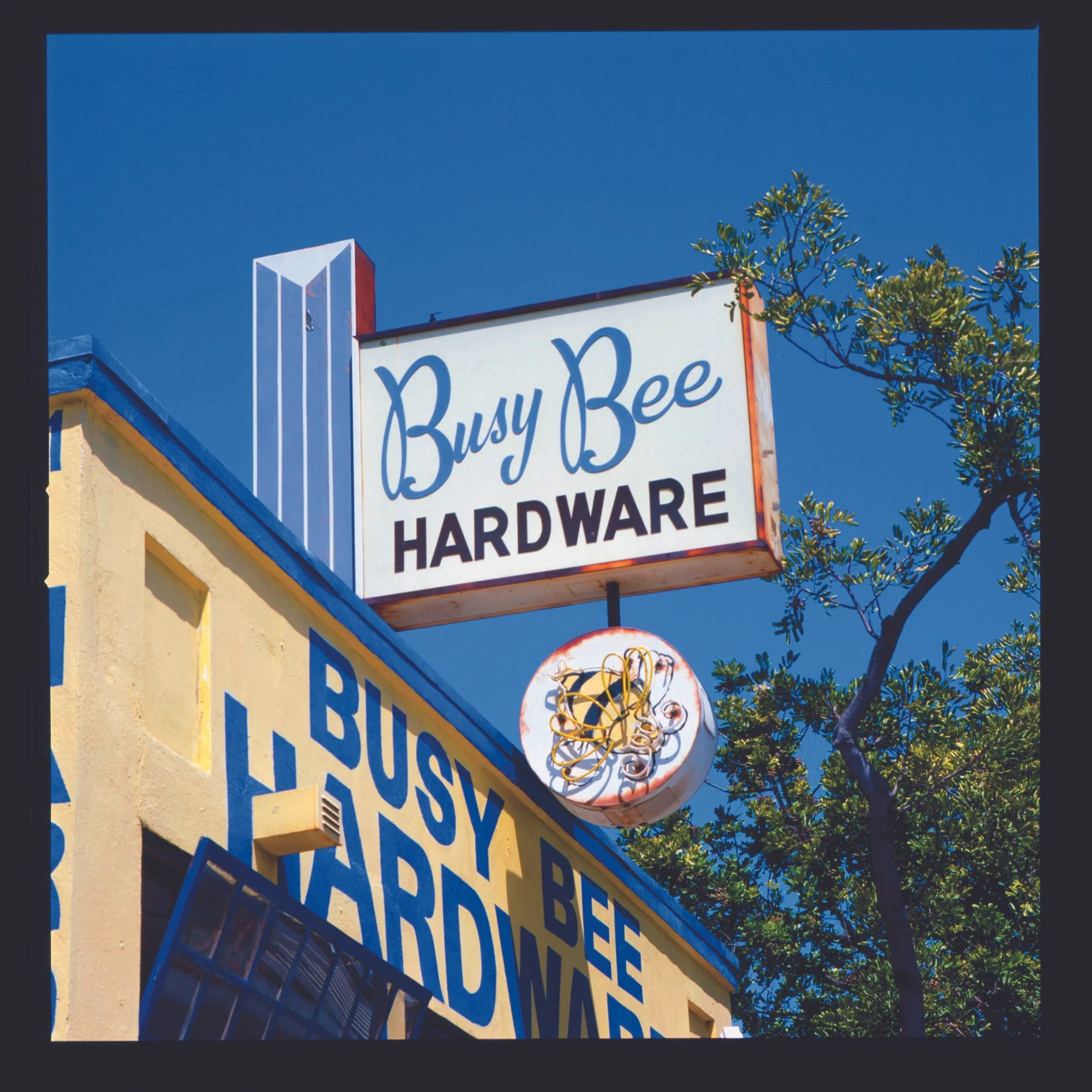

The whimsy of the signs themselves appealed to Alex Mebane. “The Santa Monica Fence Company’s sign was literally a piece of chain link fence. He grins: “So cute.” Santa Monica Radiator shop has been in business since the early 1900s, he tells me. The sign changed as the times did: “Welding moved from fixing engines to sculpting metal. They stretched that old radiator sign to look like an airplane wing!”

The placards Alex captured survived a sign ordinance passed by Santa Monica City Council in 1985, which gave businesses fifteen years to replace their “nonconforming” lollipops and other pole signs in Retro Diner font. A “blue-ribbon” panel was formed to judge the historical importance of these markers. As with most laws, there were odd loopholes. For instance, the city allowed the dealership to suspend a Mini Cooper over the sidewalk! “The irony,” Alex deadpans. A few neon masterpieces hung on, defiant and humming, like electric ghosts.

If a sign’s job is to serve as both a beckoning finger and a caption for a business, these indicators inspired Alex to wonder about the shops and buildings themselves. “I never imagined the thread I started pulling,” he says.

Alex’s connection to the city runs deep. For twenty years, he refereed youth soccer through his daughters’ leagues. “All my friends, many of whom were refs, too, still get together and play in our 60s,” he says. “It’s like a secret brotherhood of shin guards.”

He’s not trained as a historian, but has the tenacity of one. It probably comes down to a fascination with human nature and how people adorn the worlds we build. An actor, Alex also sang on Disney albums, was a grip on sets, and voiced McDonald’s commercials for about 10 years. He also has an Emmy for a children’s show he did in LA in 2015. He’s got that Southern storyteller twang, a gift for wandering off into rabbit holes that somehow all connect in the end.

Story after story of nearly forgotten people and places unspooled, anchored by the photos he took with his Hasselblad, a camera almost as heavy as the fascinating nostalgia he was chasing. “Two-and-a-quarter negatives,” he tells me with pride, “nothing Photoshopped, nothing colored. Just the real thing.”

Photo by Alex Mebane

In the back of his mind, Alex imagined piecing together these undoctored images into a book. But happily, nothing in Alex’s world goes in a straight line. Living in Texas with his family (and six backyard chickens) during Covid, Alex started watching a friend painting watercolors live on Facebook. “You can only watch so much Tiger King,” he jokes. Inspired, he ended up painting his watercolor chicken, Marzipan (named by one of his daughters). Upon hearing Alex lament his lousy early painting, one of his cousins—a fine arts painter in Richmond—suggested, “Whatever it is you’re trying to paint, paint it every day.”

That advice resonated. Thanks to Alex digging through archives, cold calling older denizens of our city, and knitting partial takes together as only a creative mind can do, we are reconnected to our municipal ancestry within the covers of his book, Signs of Santa Monica.

Photo by Alex Mebane

Even his publishing journey is full of loop de loops: Angel City Press wanted to publish his book of photographs right away; Vertell Press offered too, though they wanted to print in China—a risky proposition in 2020. The book finally appeared that July.

If Covid hadn’t happened, maybe his book would’ve launched with more fanfare instead of on Zoom. But maybe the pause gave people time to look around and see the beauty in what’s been there all along, snapshots of a city both vanishing and alive.

Photo by Alex Mebane

Through Alex’s lens, these ghosts tell the real story of Santa Monica—not the polished one in real-estate brochures, but the lived-in version that smells faintly of salt air and radiator grease. Ask about the Georgian Hotel, and suddenly you’re learning about Rosamonde Borde. An early landowner who bought two lots for ten bucks each in the early 1900s, Rosamonde deeded them to her son, Harry Jr., a World War I vet. Harry built the Georgian and later became a judge appointed by then-Governor Earl Warren. (One can, by the way, trace a line from Von Braun’s rocket experiments in Huntsville, Alabama, to the same Judge Harry—the Pregerson Exchange featured in the movie La La Land.)

But it’s his mother Rosamonde’s name, etched by her loving neighbors, that remains in the concrete outside of Goodwill on 4th Street. “She died long before the hotel was even built,” Alex explains, “but somehow her name’s still there. Santa Monica never really erases people. It just layers them.”

Photo by Alex Mebane

Another powerful woman in Santa Monica history, Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker, gave the famously large plot of land to the Veterans Association. Married off at fourteen, Arcadia outlived both her husbands—one of whom lent his name to Bakersfield. “And it’s a bust of her, not Baker, in Palisades Park,” Alex says.

This sentimental sedimentary that stacks textbook history with the cosmic humor of coincidences fascinates Alex. There’s the dental office that became Mel’s Diner and Wienerschnitzel’s partnership with Golden West Meats, which now powers all-night study sessions for college students everywhere: Taco Bell!

Photo by Alex Mebane

We chatted about how often history intersects with music. Friends recently pointed out 26 Arcadia Terrace, which graced the cover of Bob Dylan’s album Street-Legal. Alex followed up with more unsung rock n roll history: the first, unofficial concert at legendary music venue McCabe’s Guitar Shop was an impromptu performance by North Carolina folk singer Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten, famous for her song, “Freight Train.”

In fact, listening to Alex feels like wandering into a dive bar, a jazz band made of local history lighting up dark corners. But he always finds his way back to Santa Monica, the city that keeps feeding him stories.

Or rather, the stories he grabs from the jaws of obsolescence—which is how history comes to us if it comes at all—racing against the quicksand under our feet, staying the waves long enough to capture footsteps in sand before they are washed away.

He sees poetry in decay. The photos themselves tell stories, but Alex’s voice—the way he talks about them—is its own performance. In flickering neon transmitted through the decades—like the Georgian Hotel’s original double marquee, which once blinked at drivers all the way from Malibu—all it takes is a bright enough light to alert us of something worth noticing. As his project proves again and again, “Even when we die, the story doesn’t end.” Faulkner wrote: The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past.”

Alex’s Santa Monica isn’t the one in postcards. It’s the one in reflection—the hand-painted, sun-battered, occasionally buzzing reminder that cities, like people, keep telling their stories long after they’re gone.

Jessica Cole