Yuriko: Still Dancing

“My life was just my life,” Yuriko Byers says. “Duke Ellington sent us yearly Christmas cards and a poster on his birthday in July. I didn’t save them; they were simply greetings from a friend who, like most of our friends, was a musician.”

Music and dancing have always been central to Yuriko’s life—at 87, she attends our weekly Nia class. Her career as a professional dancer began with her brother, who played a palace guard in the award-winning movie The King & I, recommending Yuriko to Takeuchi Keigo. She joined another Yuriko (Kikuchi, who played Eliza in the movie) as part of the movie’s ensemble.

After filming wrapped, my friend Yuriko joined Takeuchi Keigo’s Imperial Japanese Dancers. From ages 18 to 21, she performed all over the Americas. In Vegas, the dancers opened for countless famous acts, including Miyoshi Umeki, the first Asian actor to win an Academy Award, for Best Supporting Actress in Sayonara in 1957. “Everyone got to hold her Oscar,” Yuriko reminisces.

Both Yuriko and Miyoshi, somewhat unclassifiable as neither Black nor white, were allowed inside venues, but many of the talented people who became her friends were not. Redd Foxx, Billy Eckstine, Bobby Tucker, and Nat King Cole were only permitted to sing outside of the Riviera Theatre in “the lounge.” When Nat King Cole’s fame grew far beyond the lounge’s capacity, he moved to the main stage at the Riviera. But even as the star, Nat King Cole could only enter the hotel through the kitchen.

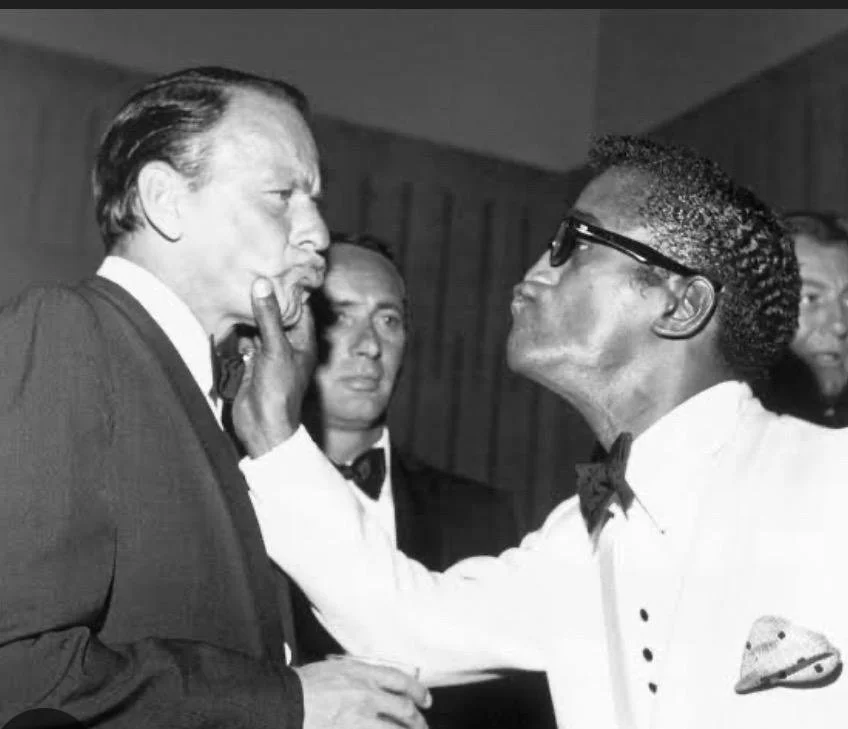

Frank Sinatra helped change this backdoor racism. “Some people are born more compassionate than others,” Yuriko says, quoting Sammy Davis Jr. “Frank Sinatra walked Sammy through the front door of the Sands, and no one was going to say no to Sinatra.”

That meant Johnny Mathis, the headliner at the Riviera, walked through the lobby, too, just like Louie Prima and Keely Smith, Red Norvo, and other white musicians. Dominos started to fall.

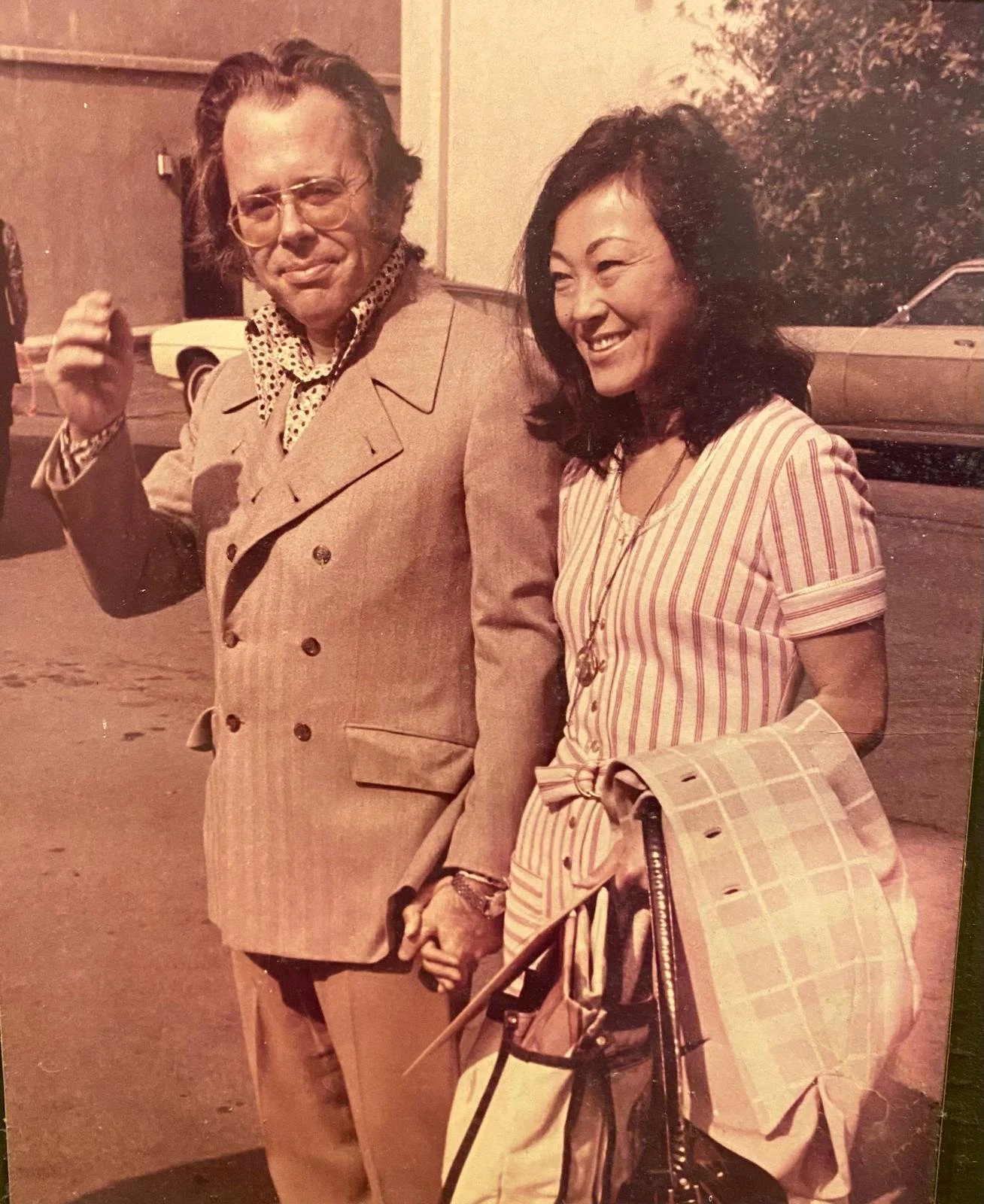

In 1958, the Stardust opened to much fanfare. Yuriko performed there with the Keigo dance troupe before she decided to move back to LA and attend LACCD. On a trip to New York City to see her dear friend Billy Eckstine in the Quincy Jones Band on Valentine’s Day, Bobby Tucker introduced Yuriko and Bill Byers (yet another Billy!).

Byers, a trombonist, had just returned from France, where he’d been Music Director for United Artists International. He’d met Duke Ellington on the set for Paris Blues. “Billy wrote an album called Impressions of Duke. Duke bought cases of those records he sent out to friends for Christmas,” Yuriko tells me.

In New York and LA, Byers worked as the band arranger for Quincy Jones, Bing Crosby, Sarah Vaughan, Count Basie, and too many famous musicians to count. His archive at the Library of Congress contains 1,167 items, including "All of Me” and "Moon River,” and Andy Williams’ “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year.”

Back in LA, Yuriko and Bill met again at Quincy’s concert at the Copacabana on Sunset. Peggy Lee, who Yuriko knew from dancing at the Mocambo in Hollywood, sang Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now) in their honor. Bill had arranged Lee’s album, Sugar & Spice.

There were many mixed relationships and marriages among their friends. Before Sinatra dated Juliet Prowse, he dated Yuriko’s roommate, Yashi Muneko, otherwise known as “Miss Tokyo of 1957.” Charlie and Chan Parker, Quincy Jones and all of his wives (and mistresses!), and Sammy Davis Jr. and May Britt, to name a few.

Yuriko and Bill married on July 1st of the same year with her family’s blessing. “I had the most amazing parents,” she raves. “They were loving, supportive, and didn’t interfere in our lives. They knew all four of their kids as individuals. As Christians, they saw themselves as guideposts and guardians, but not teachers.” Her equally loving grandparents only spoke Japanese. They had emigrated to Sacramento and owned a boarding house there. They were already well-versed in the fluidity of class constructs: Yuriko’s family, Gengis, are in the same clan as the female author of The Tale of the Gengi—the first book written in novel form. It’s the story of a prince who refused to renounce a commoner, Gengi Michiko, so his royal family made up a lineage for her. Yuriko’s daughter is named Michiko for this reason.

Her family’s open-mindedness contrasted sharply with the racism Yuriko witnessed against Black musicians in Vegas and Japanese-Americans forced into internment camps during the Second World War.

During the War, Yuriko and her family lived in Oklahoma: “We were maybe the only Japanese family in Oklahoma City.” She remembers one Sunday her dad returned from the market, cautioning them not to go to school because their country was at war with Japan.

But when they went back to school, no one said “go home” or hissed at them, which happened elsewhere. In fact, no one in her family went to the camps. She thinks this was in large part due to her grandfather and uncle teaching Oklahoma farmers about Japanese irrigation tactics. Nothing was more important than bringing water to the Dust Bowl.

Though her family didn’t directly suffer, they mourned the plight of others. “So much property was stolen from the Japanese,” Yuriko tells me. “From fishing operations in Venice row houses to fertile farms in Palm Springs and Palm Desert.”

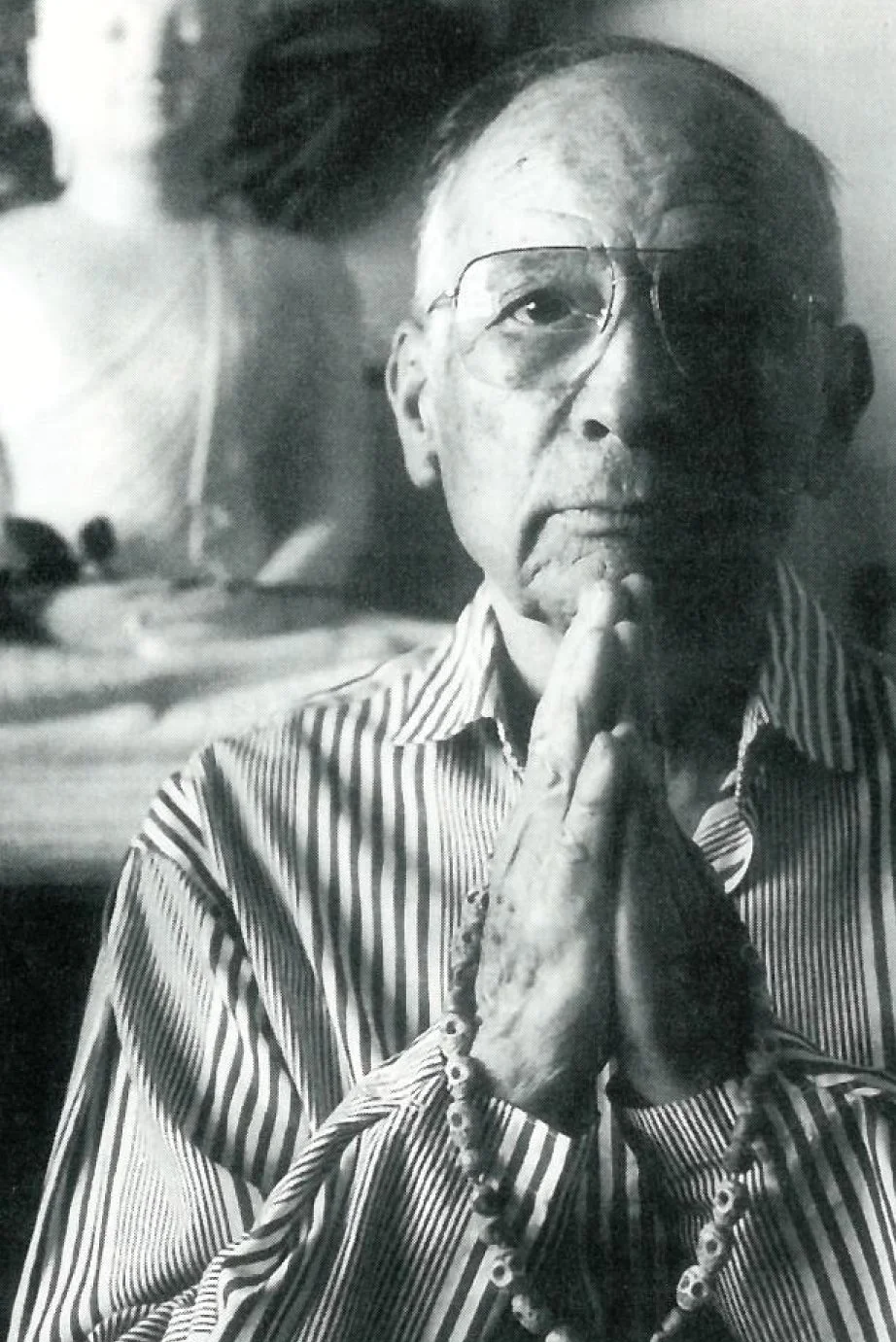

An important ally during this time was Julius Goldwater, known as Reverend Subhadra, a Jew-turned-Buddhist who spoke Japanese. Allowed to keep the Buddhist temple open during internment, Goldwater drove back and forth from Tule Lake and Manzanar camps delivering items requested by his parishioners. “So often what looks like a tragedy in one respect is a gift in another,” she says. “Meeting Reverend Subhadra was an amazing experience, knowing what he did for my community.”

Yuriko muses: “Japanese people played the long game. We’re still here.” If she goes to a hospital and someone signs her in as Japanese, she adds -American to it. Her parents were naturalized American citizens, so what else would she be?

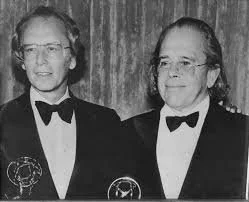

Byers became Basie’s arranger after Neal Hefti, who wrote “Girl Talk” and the Batman score, switched to movies. “Billy devised a system he called ’wood-shedding.’ Billy wrote the charts or songs. He and I traveled with Basie and his band while they played, honing the music until it was good enough for recording.” One of these songs was Yuriko. “Basie’s band infused their characters into Billy’s arrangements. Similarly to us dancers personalizing choreography,” Yuriko says.

Bill Byers received nine Emmys. He inspired the creation of the Tony category for orchestral arranger. Yuriko shared that there was a waiting list for musicians wanting to read Bill Byers’ score for the show City of Angels. The arrangement was so beloved, the show’s musicians started a petition to add it to the Tony category. “People used to wait at the end of the show (including Liza Minnelli) to talk to Billy and the musicians,” Yuriko reminisces. Byers wasn’t interested in awards; the work was his love. Or, more precisely, the next show, album, and song. “Once I finish something, it’s over. The awards are for them, not me,” he told Yuriko.

Bill Byers didn’t have a publicist. Few of the stars of that time did, which underscores their humility and their passion, but renders them less known decades later. We want to bestow honor for their essential contributions to American culture. “It’s not name-dropping, these are our friends,” a friend once assured Yuriko.

The couple had many wonderful decades together and three children. Sadly, Bill died young, on his 69th birthday.

“All we are is a result of what we have thought,” Yuriko says. “Life filters through our brain. Our focus is consciousness.” She adds, “Billy understood this empirically.”

Yuriko knew most of the greats, was happily married to one, and continues to dance through her life. I’m honored to share some of her stories. In this town (and anywhere), we truly don’t know who walks among us, brimming with marvelous tales. For a recent interview with Yuriko, click here.

Jessica Cole