Joyful Remixes: Silkscreening and Music

“The first thing you learn when you print a silkscreen is there’s always a chance you’ll make a mistake,” Kenny Langen laughingly tells me. No matter how carefully you line things up, how evenly you pull the squeegee, how much experience you think you have, something can go wrong. A line breaks. Paint bleeds. Color lands where it shouldn’t. And instead of fighting it, you learn to bring extra paint—not just to fix the mistake, but to make it look intentional.

That spirit carries into the technical side of the work, too. Amateur silkscreening, he insists, is easier to see and do than to explain. You learn by watching, by trying, by messing it up. He uses special paper with coding on it, mirror-imaged for the screen, a semi-professional method that still feels accessible. If you don’t squeegee the paint just right, it won’t work exactly as intended, but you figure that out by doing. And often, the surprises are happy accidents.

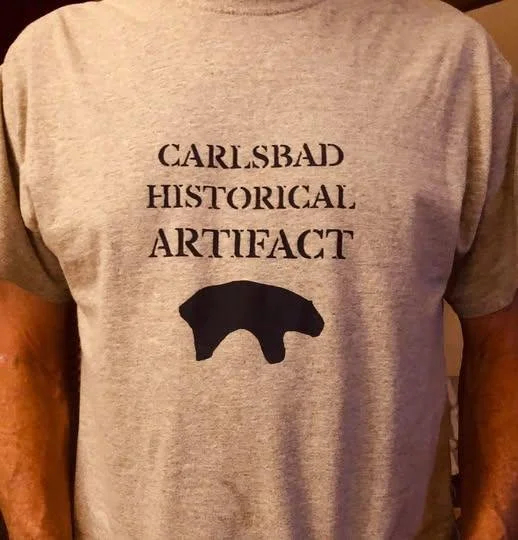

He likes Speedball silkscreen paint because it doesn’t dry too fast. That means you can keep loading color onto the screen, pull after pull, without it clogging up. Save the same screen, and you could easily print another hundred shirts. When he volunteered with the Carlsbad Historical Society, he did two batches of forty shirts each. He stacked them carefully, cardboard in between so the paint wouldn’t soak through. It’s practical knowledge, learned over time, shared freely.

For instance, his sister-in-law made a small mosaic of a hummingbird. Kenny traced it, turned it into a silkscreen, and printed it onto a T-shirt he gave (back) to her: her own design, transformed, wearable. Who owns the image at that point? The person who made the mosaic? The person who traced it? The screen? The shirt? It doesn’t really matter. What matters is that it comes back around, shared.

Just as silkscreening blurs the line between mistake and intention, so does music in Kenny’s life. Every week, eight to ten people gather at his house for a jam session. His wife sings and plays guitar. Kenny handles percussion and runs the recording setup. The house becomes a kind of vocal sound booth, with eight tracks recorded simultaneously, trying to capture life in song and in flight.

Sometimes the paint doesn’t just misbehave; it explodes. It squirts everywhere, splashing the surface in a way no careful plan could have predicted. That’s when silk screening starts to feel less like a visual art and more like music. There’s rhythm, timing, improvisation. You respond in the moment. You listen to what’s happening and adjust. The mistake becomes part of the composition.

Over the years, Kenny has produced several albums at what he named Brother Rock Demo Studios. Over the years, four- and five-piece bands have emerged from that garage studio. His daughter Livi, of the L.A. band Cool Knife, started there, along with other young musicians who went on to win San Diego Music Awards. The jam sessions aren’t about perfection. They’re about showing up, listening, responding, playing, harmonizing. Basically: silkscreening notes onto the air.

That same collaborative energy fueled Roots and Sprouts, Album #2, now streaming everywhere. More than thirty musicians worked on it. One song was produced by Ron Blair, bassist from Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Another track, “Monkey See Monkey Do,” carries that lineage forward, borrowing and building, never pretending to appear out of nowhere.

Kenny recorded his daughter, Catalina—Civic Wellbeing rockstar and Executive Director of the Human Relations Council—for a track on the album, “Gotta Make Some Time.” By stripping down one voice and layering her voice back in, Kenny seems to have almost bent time and reshaped the air. For a few years, Cat has sung with the Santa Monica Chorus, which, Kenny explains to me, is Sweet Adelines meets radical inclusivity.

Kenny doesn’t separate music from visual art, or art from community. “It’s all the same practice, really,” he says wisely. You show up. You make a mess. You fix what you can, and you turn the rest into something that looks like it was meant to be there all along. You let the paint stay wet long enough to keep making more prints. You invite people in. You remind them that they don’t need to be artists to make something meaningful.

Kenny doesn’t even call himself an artist. He shrugs that off quickly. What he does is show people how to have fun. How to make something together. How to stop worrying about originality and start enjoying the process.

“Where is the origin of all knowledge, really?” he asks. “Few of us have original thoughts.” Images come from other images. Songs come from other songs. Ideas are borrowed, echoed, transformed. The joy is in the remix.

He prefers acrylic paint for the smaller 8”x 10” screens we’ll be using with him this Friday at Coffee & Connections. There’s nothing precious or intimidating, he promises me, about the process. He designed a portable, flexible setup for spontaneous workshops and fun group experiences.

Jessica Cole